Baum and the Prague Circle

Oskar Baum moved to Prague in 1902 after having completed his education in Vienna. At the time, the city itself had about 210,000 inhabitants, but the total population was around 600,000 including nearby settlements such as Smíchov, Žižkov and Vinohrady.

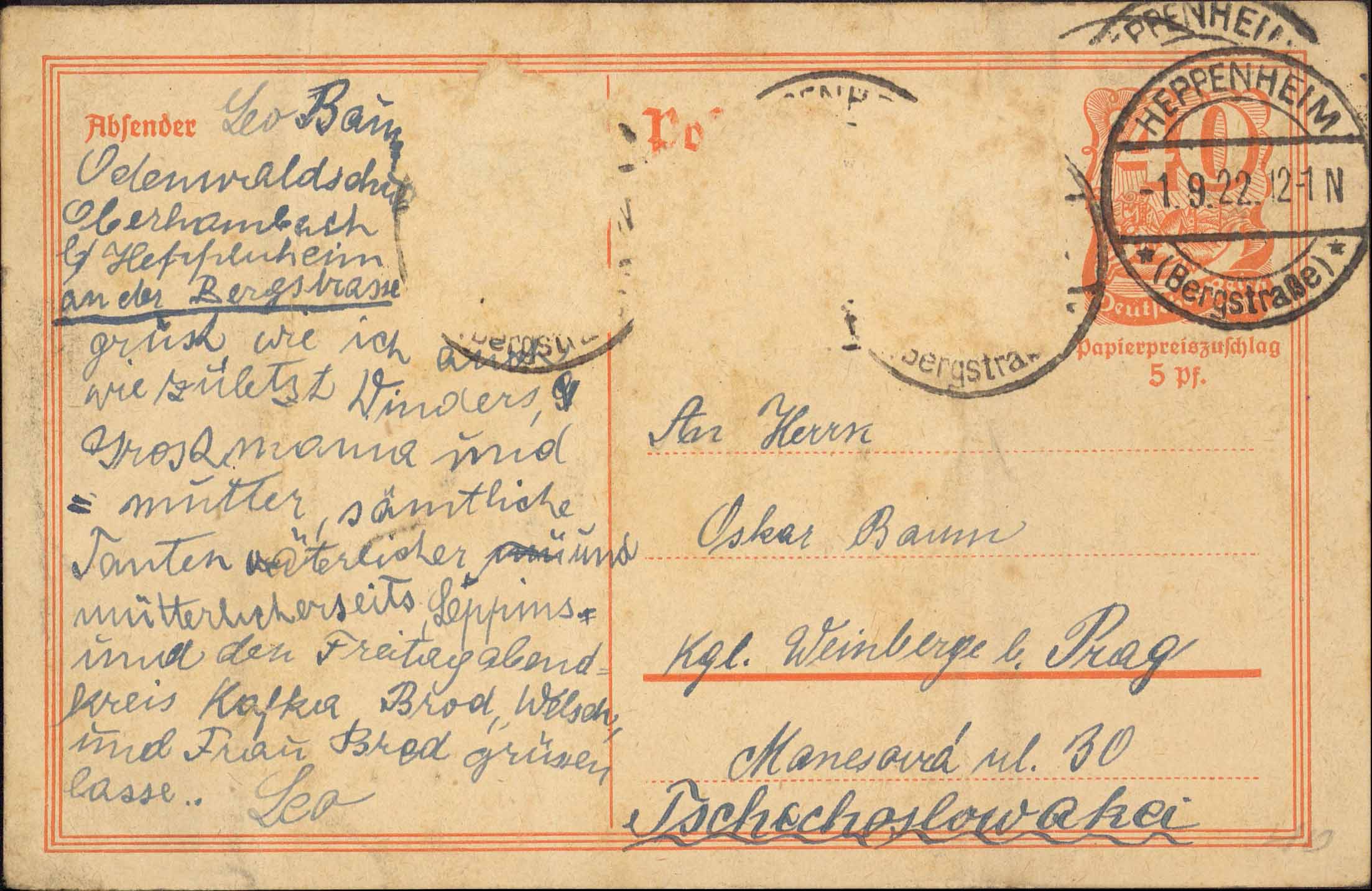

This transformation also affected the local Jewish population. Especially after 1859, when freedom of movement was allowed, Prague's Jews tried to escape from the former ghetto located in Josefstadt. In 1843, 95% of the Jewish population lived there (5,929 residents); in 1880, this number decreased to 45% (4,798 residents), and in 1900, two years before the arrival of Oscar Baum in Prague, only 24% remained there (2,198 residents). At that time, wealthy Jews began to move to new bourgeois neighborhoods, particularly Královské Vinohrady (Königliche Weinberge), which became the center of Jewish social, commercial and religious life (Frankl et al. 2021: 126-129).

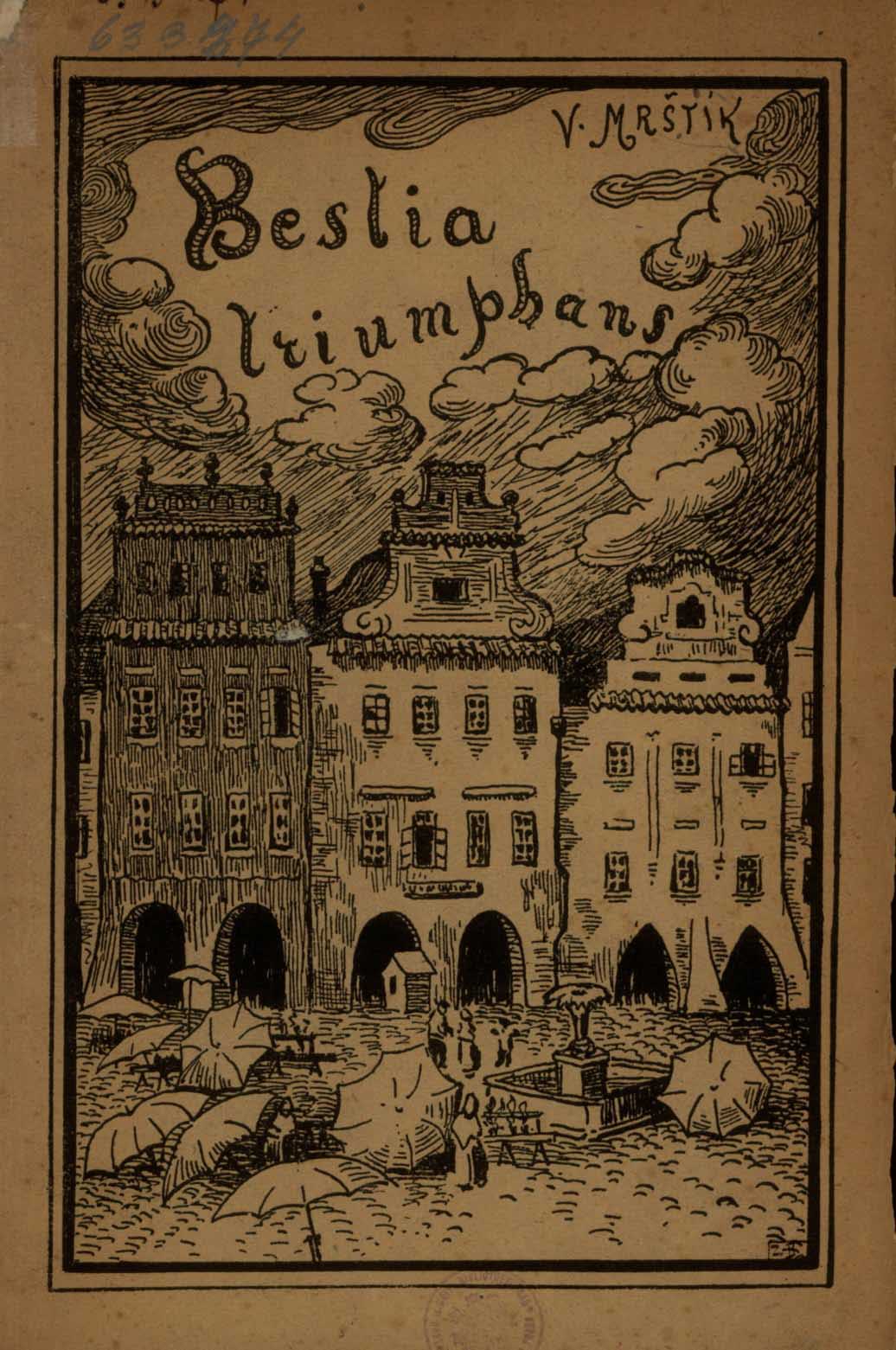

The cover of the book Bestia triumphans (in Latin: Victory Monster), published in 1897 by Vilém Mrštík. It was written as a critique of the course and extent of the redevelopment of the historic parts of Prague that had been underway since 1893. It mainly concerned Josefov and part of the Old Town. The redevelopment plan was then gradually extended to the area of the Old Town and the Lesser Town. A number of historians and writers, led by Mrštík, rebelled against this practice. In his text, Mrštík pointed to the barbaric destruction of monuments in the interests of the construction and investment groups of the time. What is interesting about this criticism is that it was directed at the demolition of monuments in the Old Town and the Lesser Town, not at the Jewish Josefov.