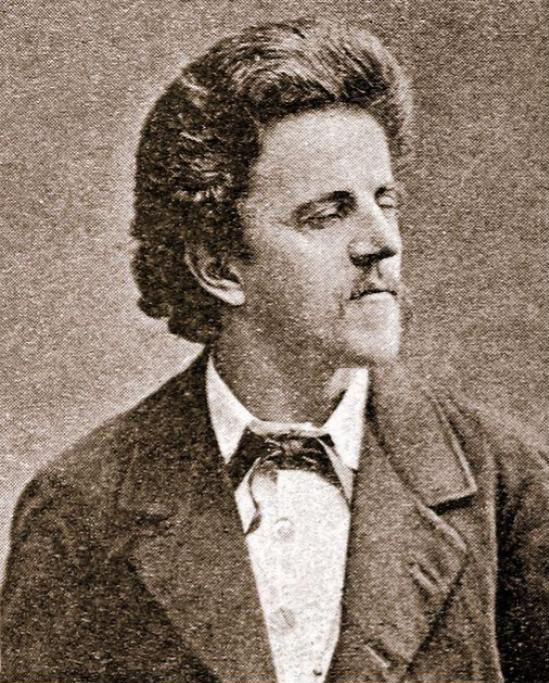

Baum in Vienna

Oskar Baum moved to Vienna in 1894 and spent 8 years there during a period of rapid changes and sudden population growth. At that time, Vienna was the capital of huge empire that included the Czech lands of Bohemia and Moravia. In 1880, the city had 726,000 inhabitants, and over the next decade, this number increased to 1,365,000 due to the incorporation of the surrounding suburbs. By 1910, the city's population had reached a population of 2,031,000, the highest number in history. Around the turn of the century, more than 20% of the population were immigrants from Bohemia and Moravia. Approximately ten percent of the population had a Jewish background (Kiss 1937).